Minoan Religious Imagery

Very little survives of Minoan writing, and what does is largely undeciphered owing to our ignorance of the Cretan language and how they employed their writing system Linear A. As a result, we’re left in the intriguing position of attempting to understand Minoan culture, including their relations with the gods, almost entirely through the surviving imagery excavated by archaeologists. These images include murals and frescos; rings and seals that were intended to make a symbolic impression in clay; and figurines left behind in graves.

Since these images can’t speak for themselves like literature can, they’re especially prone to having the viewer’s own thoughts mapped onto them. Minoan art is often dangerously overinterpreted and misinterpreted, especially given that modern viewers tend to assume—often wrongly—that ancient art of unknown purpose is probably religious.

For example: the imagery we have of “bull leaping” might be interpreted as dominance over the forces of nature, given the way bulls often represent the power of nature in ancient cultures. But its significance might just as easily be as sport, entertainment, a rite of passage, and so on.

Source and commentary: Marinatos, Nanno. 2004. “The Character of Minoan Epiphanies.” Illinois Classical Studies 29: 25-42.

Ecstatic Epiphany

One type of Minoan religious scene shows a man or a woman shaking a tree. Ever since Sir Arthur Evans, the excavator of Knossos and the founder of Minoan studies, these scenes have been linked to the phenomenon of “ecstatic epiphany.”

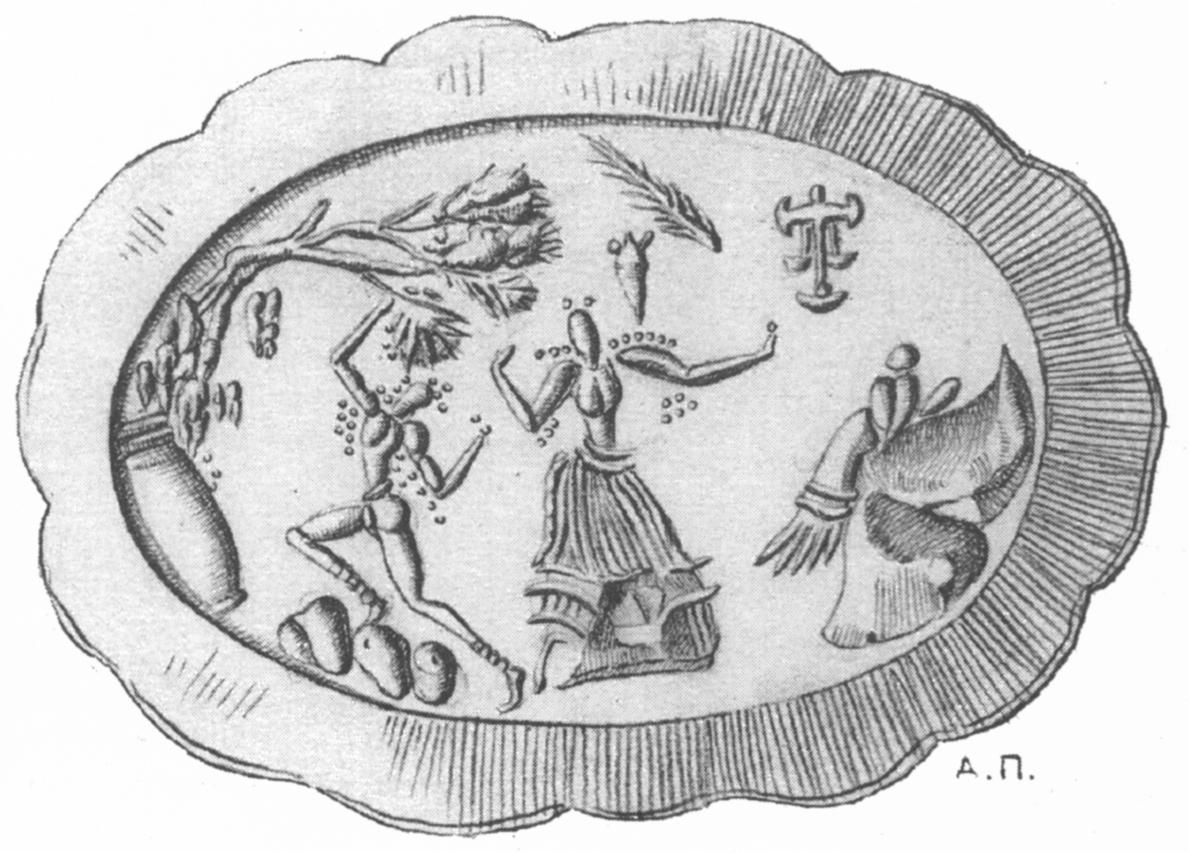

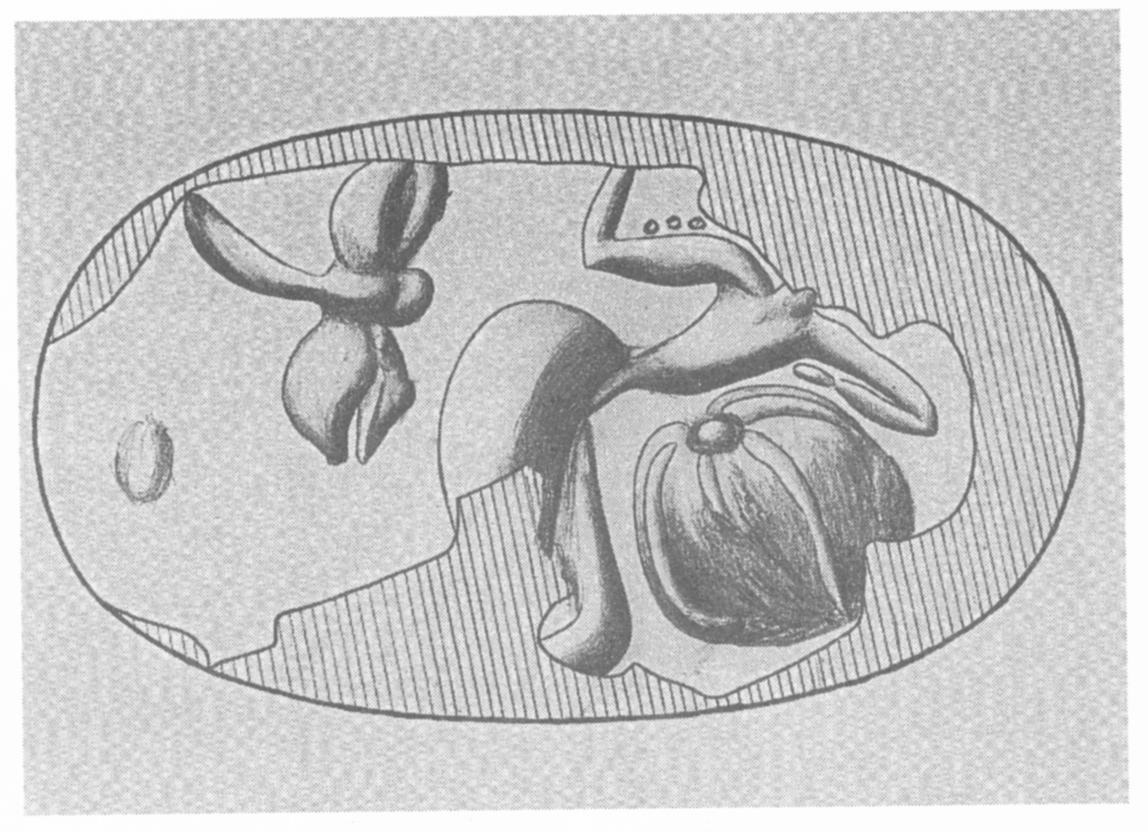

Figure 1

Let us start with Evans’ description of one ring found in a tomb at Vapheio, Peloponnesus (Figure 1): “On the left of the Goddess a male attendant plucks a fruit from the sacred tree… this is a special ritual moment. It is the juice of the sacred fruit, like the Soma of the Vedas, that supplies the religious frenzy, and at the same time implies a communion with the divinity inherent in the tree.”

Three points are of interest in Evans’ interpretation. First that the man shaking the tree is a mortal in a state of religious frenzy; second that if a worshipper touches the tree, he/she sees a deity; third that the figure in the center is a goddess. The word “frenzy” may require re-examination and there is no evidence that the juice of the fruit was collected, as Evans thought. These remarks apart, he was essentially correct in his perception.

Twenty years later, the Swedish scholar M. P. Nilsson … differs from Evans in that he identifies the central figure as a mortal. If the epiphany of a goddess were intended, he argues, “it is more than astonishing that the votaries should turn their backs on her; consequently she is to be understood as a devotee performing a sacred dance in the tree cult.” Nilsson adds the interpretation that all the figures (whom he identifies as mortals) are dancing in an excited and violent movement.

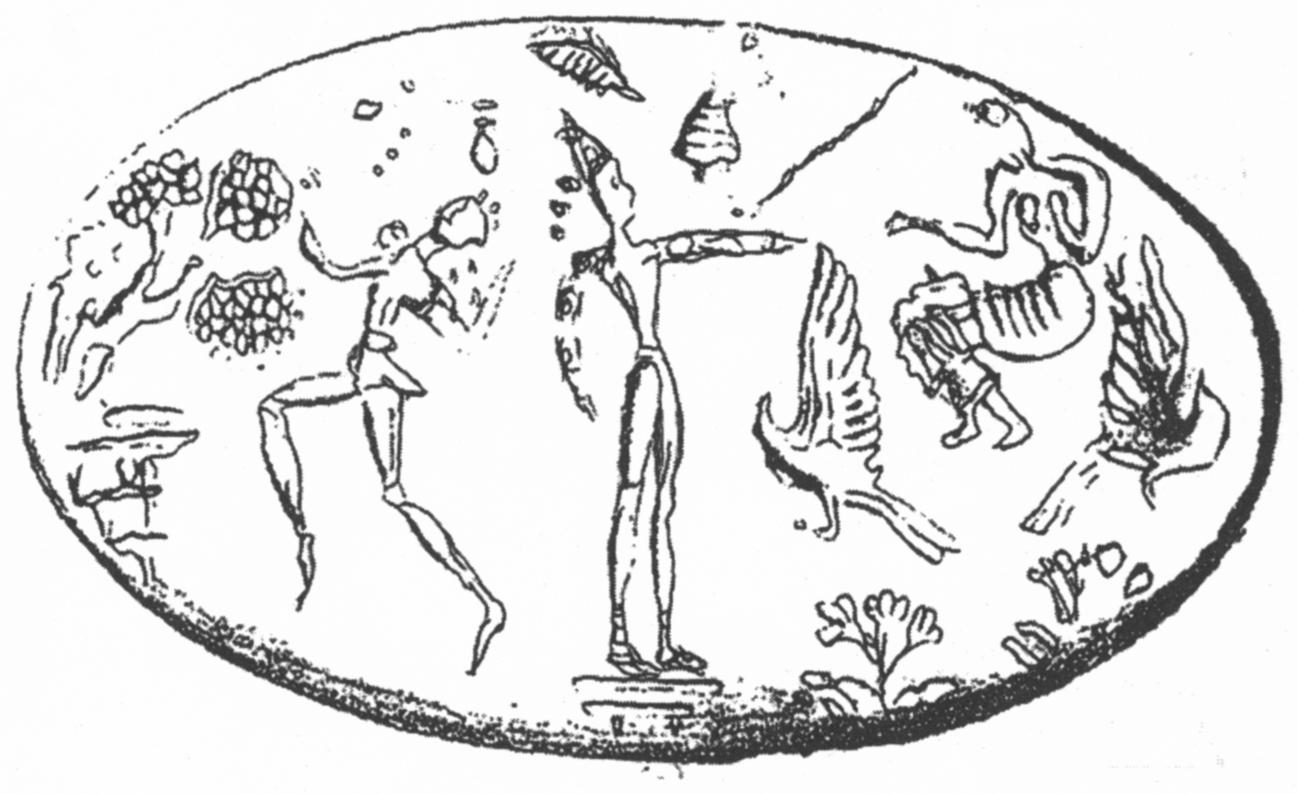

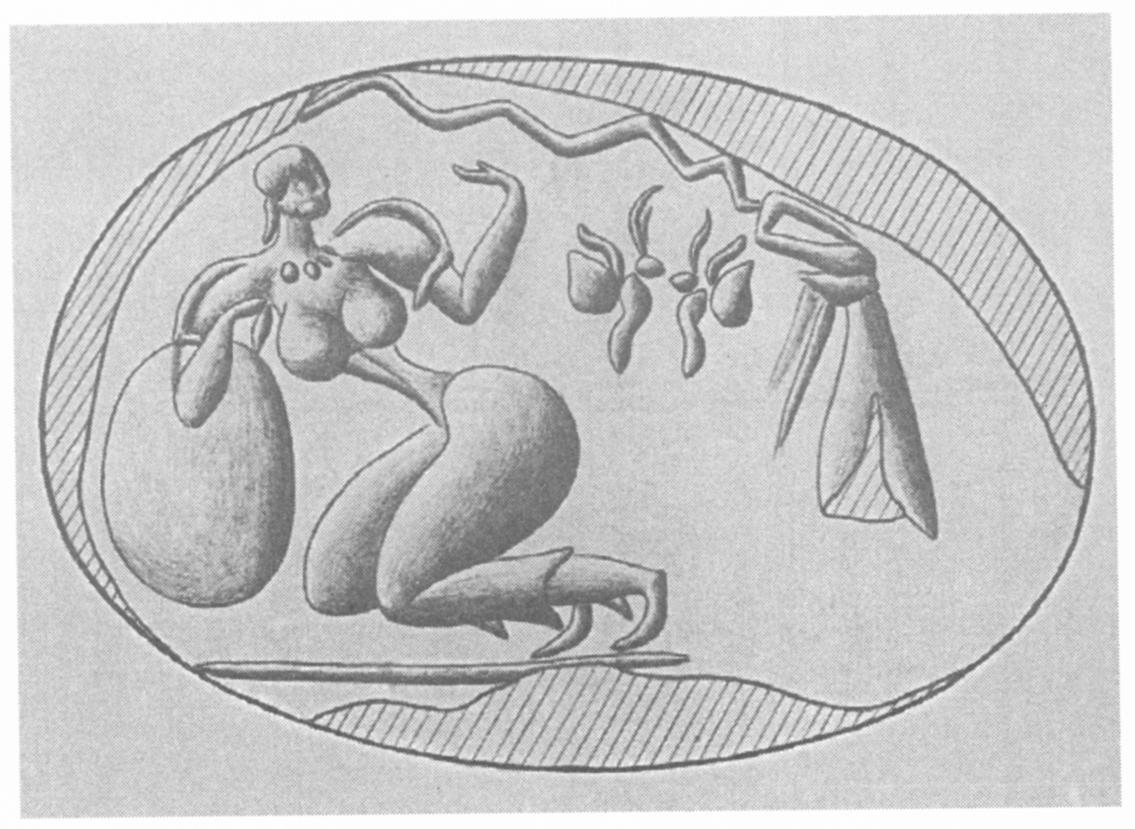

Figure 2

About the Mycenae ring (Figure 2) Nilsson writes: “To the right there is a man in energetic movement; almost kneeling and turning his head around, he grasps and bends down the stem of a tree which rises from the construction… In the middle is a woman with flounced skirt and open bodice with her hands held towards her waist. This attitude belongs to the dance.”

He concludes that we see here an ecstatic or orgiastic scene of the tree cult together with dancing. He repeats his conviction that the figure in the middle is a not a goddess but a mortal. Friedrich Matz followed Nilsson and was of the opinion that the central female figures were mortals. For these scholars there was no anthropomorphic epiphany involved in the ritual of the shaking of the tree.

In more recent years, however, the pendulum has swung again to Evans’ side. The central figure next to the man or woman bending the tree has been recognized as divine [in all of these scenes].

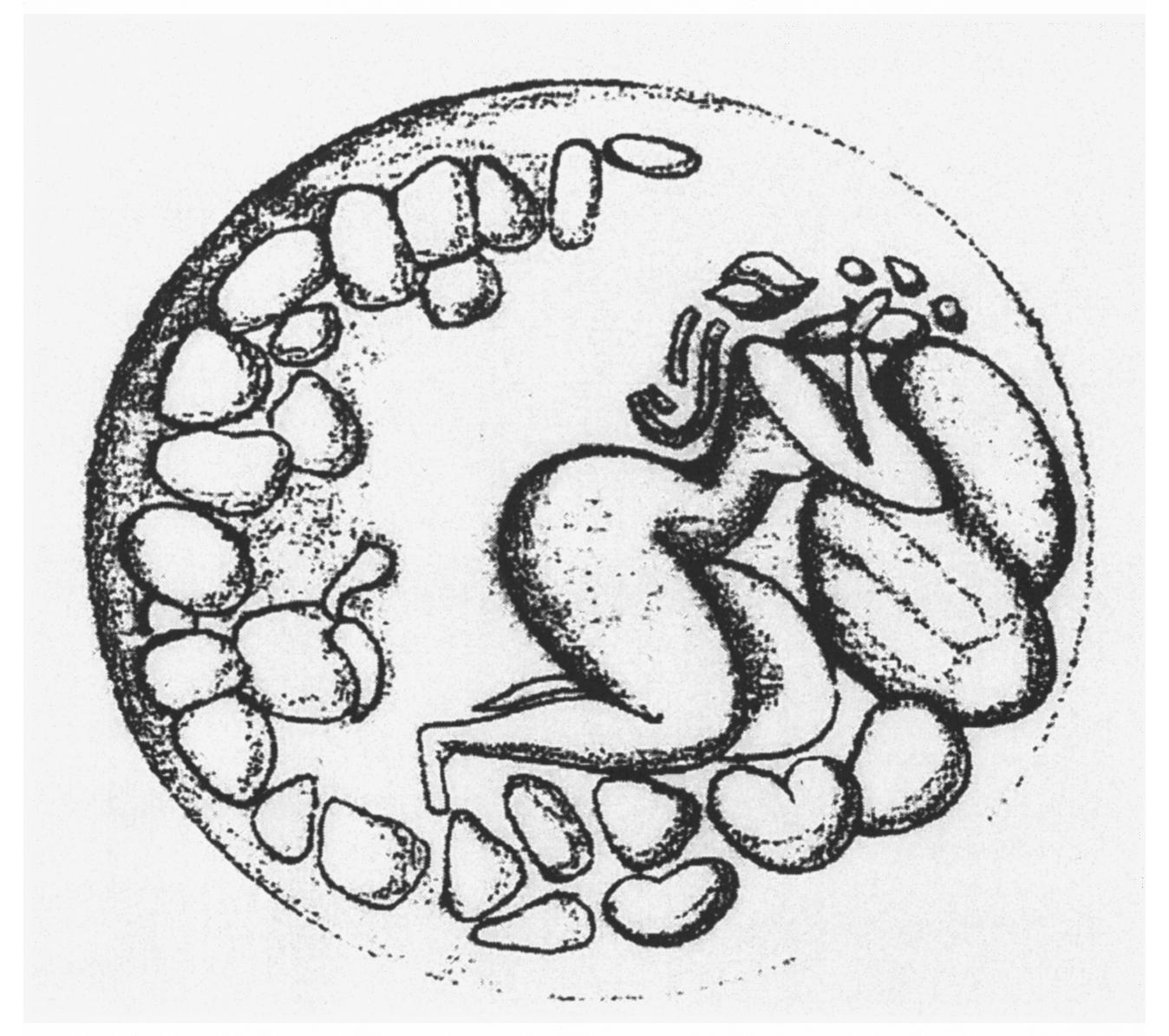

Figure 3

The discovery of the Archanes ring on Crete (Figure 3) aided this identification.

John and Effl Sakellarakis, who found it, argued that the central figure is a goddess, whereas Wolf-Dietrich Niemeier provided systematic argumentation by creating a typological classification and analysis of all the relevant scenes.

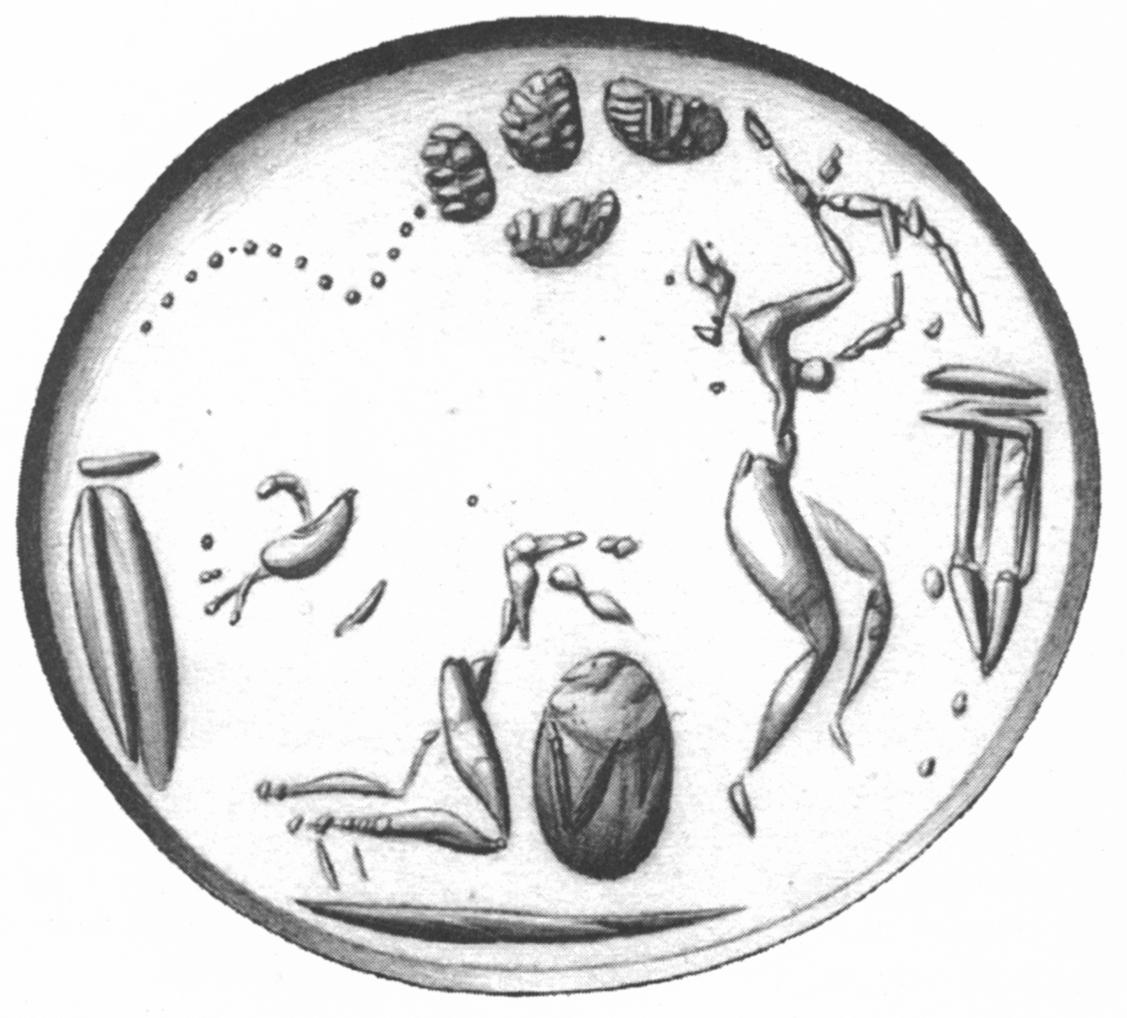

Figure 4

An even more recent discovery provides absolute proof of Evans’s view that the central figures are divine. A ring excavated in a tomb at Poros, near modern Herakleion in Crete by Nota Dimopoulou, shows one more instance of a man shaking a tree (Figure 4). The ring merits detailed description. A minute figure floating in the sky is depicted in the upper left section of the field. The gender is female to judge from her skirt with horizontal stripes. She faces a large goddess who is shown as seated but is nevertheless hovering in mid-air. The seated divinity is flanked by two flying birds; the iconography has a parallel on a ring impression from Knossos. How can a seated goddess hover? The lack of a throne makes the representation paradoxical and suggests that it is a vision. At the center is a male figure standing on a podium. The excavators suggest he is a god, and this is probably right. Thus we have here two if not three divine figures: the only unquestionable mortal is the man who shakes a tree on the side of the ring’s impression.

To sum up: First, the figures who shake the tree are mortals not gods; second, tree-shaking (or bending) results in divine presence (Figures 1-4).

Figure 5

Note that the ritual may be depicted as an activity in its own right (on a seal not a ring), which means that it was a ritual action of some importance (Figure 5).

However, the issue of tree worship has yet to be addressed. How is the divinity summoned? I would argue that it does not signify tree cult as Evans and Nilsson and others thought, driven by their conviction that Minoan religion had primitive traits. There is no cult of the tree on our rings because the worshippers do not make offerings to it; they simply use it as a medium of communication. This too requires an explanation, however, because it is not evident why trees should have this function.

In my view trees mark the habitat of gods on earth and constitute focal points of a sanctuary. They have a similar function in many religions (certainly so in the Hebrew Bible cf. Deut. 12:12) even in modern times. … In Minoan Crete, the epiphany of a god is often linked visually with a tree as on a ring from Kavoussi (CMS II.3.305) where a hovering deity is greeted by a female figure.

By bending or shaking the tree the worshipper attracts the deity’s attention; this act does not constitute tree worship. It is rather a ritual denoting ecstasy. The ecstatic worshippers may be of either sex. The deity may be a single anthropomorphic goddess, as on the rings of Vapheio, Mycenae and Archanes (Figures 1-3), or several gods, as on the Poros ring (Figure 4).

The epiphanies are witnessed by mortals and linked to rituals. However, one remark is important: none of the figures bending the tree seem to gaze at the god directly. Even when their head is turned, they do not face the divine figure. Perhaps they hear the voices of gods or sense their presence. There is an explanation at hand: seeing the god may be dangerous. Hera says in the Iliad that gods are harsh when they appear clearly to men (20. 131). In Exodus 33:17-20, Yahweh warns Moses that he cannot see him, and live.

Sleeping on a Stone

We now turn to another ritual depicted on the rings where the worshipper is not active but passive. A man or woman kneels and rests his/her body on an oval rock. (Figures 6, 8-11).” What does the posture signify? It has been interpreted as mourning by the founding fathers of Minoan religious studies. The imagery was interpreted in the light of Near Eastern myths and rituals relating to the death of the young god. The oval stone, according to Evans and A. W. Persson, represents the tomb of the dead god on which the mortal worshipper mourns.”

The above scholars were probably misled. Mourning is rarely expressed as a passive state of sorrow in ancient art. Instead, the mourners beat their chest or tear their cheeks and pull their hair.” We now turn to the more widely spread interpretation that the kneeling figures worship a baetyl. Nilsson, for example, interpreted them sometimes as mourners and other times as worshippers; perhaps he did not quite make up his mind. Behind his theories was the unspoken assumption that stone worship is primitive and animistic. I would like to argue that there is no more stone worship than there is tree cult.

Figure 6

On Figure 6, a seal stone from Knossos, we see a woman resting her body and head against a rock. This stance can be plausibly interpreted as sleep, rather than mourning or worship. Although each culture develops its own visual codes, a comparison with medieval painting may be helpful because it reveals similar conventions: a sleeper has a dream vision as he reclines against a rock. A crucial feature is the resting position of the head, for no sleeper will hold his head erect. …

These visual formulas in medieval art illustrate the importance of supernatural visions and how artists sought to express them. Viewed in this broad context, the Minoan sleeper on the stone is a comprehensible visual template. Sleep is a state that induces vision because it is connected with dreams. This explains why on most of the Minoan rings the head of the worshipper is turned backwards towards the deity: the dreamer “sees” the god and even greets him/her by an extended arm (Figures 9-11).

Figure 8

Let us now turn to the Hebrew Bible. In Genesis 28:11-13, Jacob has a vision of God (italics mine): “And he [Jacob] took one of the stones of the place, and put it under his head, and lay down in that place to sleep. And he dreamed. And behold, a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven. And behold, the angels of God ascending and descending on it. And, behold, Jehovah stood above it…” (ASV). Attention to the vision is drawn by the verb idou (“behold”) in the Septuagint translation of the text. The verb need not be taken literally as “seeing.” Nevertheless, it is a pointer to the vision and may be viewed as the verbal equivalent of the device of the turned head of the worshipper on the Minoan rings. Most striking is the presence of the stone in both the dream and the rings. Jacob sleeps on a stone; when he wakes up he anoints it with oil and calls it the House of God: Bet-el (baetyl; Gen 28:19).

The rock on Minoan rings was in all likelihood a cult monument (Kultmal) within sanctuaries and (like the tree) it designated a holy spot. This was the place where the deity might appear, just as the abaton was the designated place where the patient saw the god in his sleep in the later Greek sanctuaries of Asclepius or the hero Amphiaraus (Herodotus 8.134).

Figure 9

Note that the tree and rock associated rituals may co-exist in one and the same scene (Figures 3, 8, 9). Were the rituals complementary? It seems that they depict two alternative forms of prophecy: ecstasy and incubation.

One (the shaking of the tree) involves possession of the body. The other (sleeping on a rock) entails a passive state although the spirit may be wandering. There is a further distinction: only the sleepers may gaze at the gods, whereas the figures who shake a tree never do. This is evident when we look at the rings from Archanes and Kalyvia where both rituals occur (Figures 3, 8).

The distinction between those who see—the sleeping figures—and those who sense or hear the divine presence—the shakers of the tree—is evident.

The Nature of the Vision

What do the humans experience if they shake the tree or sleep? The experiences vary. Sometimes there is a single goddess who stands in the center, as in the rings from Vapheio (Figure 1), Mycenae (Figure 2) and Archanes (Figure 3). On the Poros ring (Figure 4) the man who shakes the tree sees several deities. The narratives differ and this is perhaps what makes each vision special and unique. In what form do the mortals see the gods? On Figs. 1-4 the divinities are anthropomorphic. But why do the goddesses have their hands on the hips or have one arm extended (Figures 1-3)? I follow Evans’ suggestion that the gesture indicates a twirl of the type that dervishes engage in. While Evans thought of the twirl as a dance, I rather think that it is the slowed-down phase of the swirling movement of gods who have just descended from the air like whirlwinds. Alternatively, the adorant sees deities as stationary images in their own sphere, as on the Poros ring, where the seated goddess hovers above a crocus field facing a god/statue on a podium (Figure 4).

However, what mortals see is not always an anthropomorphic vision. On the Sellopoulo and Phaistos/Kalyvia rings (Figures 8 and 9), the men who lean on a stone see birds (see Burkert in this volume). On the Archanes ring (Figure 3) the vision includes two dragonflies and other symbols such as an eye next to an oversized goddess.

Dragonflies seem to be important: on a ring imprint from Zakros (Figure 10) the visionary sees one huge dragonfly. On a similar impression from Hagia Triada (Figure 11) a woman sees a pair of dragonflies and a sacred garment (perhaps a skirt).

The key to the dragonflies maybe is to be found on a wall painting from Santorini/Thera, which represents a Minoan goddess with a dragonfly necklace around her neck. Whether the insect was considered a manifestation of the deity or a messenger cannot be decided.

Figure 10

Figure 11

Disqus comments disabled.