Critical Thinking Writing Project

For the last part of the semester we’ll work through a set of short assignments that understanding and analyzing evidence

For this project, you’ll pick a document from history and talk about what you think it really tells us, giving examples of your reasoning from the text you chose and other sources related to that time and place.

Here are the steps involved:

| Due by | |

|---|---|

| A. Choosing your document | Monday, November 13 |

| B. Summary Write-Up | Monday, November 20 |

| C. Annotated Bibliography | Monday, December 4 |

| D. Analysis Write-Up | Monday, December 11 |

B. Summary Write-Up

Read through your document and summarize the story it tells in your own words.

- Answer the Summary Questions below.

- Read through the document and describe what is happening in each scene. Use your own words.

- Your only source for this write-up should be the text of your document. You don’t need to do any other research.

- You don’t need to try to analyze or interpret the author’s intent, motives, or meanings—that comes later. For now, just summarize.

- Take note of the Summarizing Process suggestions and the Summarizing Tips below.

- Formatting: Your Summary Write-Up should

- Be double-spaced

- Have standard 1-inch margins and a standard font and font size

- Have your name, the date, and a title (for example, “Summarizing XXXX”, where XXXX is your document) at the top, or on a separate cover page

- Length: Your Summary Write-Up should be about one full page of writing, double-spaced, or more if necessary. This is about 350-400 words.

Due date: Monday, November 20

Document Summary Questions

Primary sources are the most direct and most powerful way to connect with people and events of the past. But primary sources must be interpreted, because every source originates from a certain point of view and is intended for a certain audience, and therefore tells only part of the story. Our job is to figure out what part is being told, how it relates to what else we know, and what’s being left out. You should ask yourself these questions each time you encounter a primary source.

- Who wrote this document, when, and where? In some documents, as in a course reader or handout, you might be provided this information in the headnote to the source; or it may be in the introduction to the edition you’re working from. The who, when, and where provides the context you need to get beyond the document’s face value. Some documents have no known author, but you can still say something about them, like “A person from ancient Egypt.”

- What type of document is this? Primary sources come in all types, and which type tells us something about what was going through the author’s mind when he or she wrote it. For example, a newspaper article would normally be written to be a concise and informative communications to many readers, while a private diary entry is probably more candid and informal, intended to be seen by few or none, or perhaps intended to be read by the writer’s family or descendants. (Although this discussion is framed largely in terms of written documents, all primary sources—artifacts, recordings, graffiti, and so on—can be treated with these same steps.)

- Who is the intended audience of the document? Most documents are intended to communicate ideas and viewpoints to a person or a group. Authors tailor their arguments to their target audience, sometimes without realizing it, using their knowledge of the target to elicit the best response. Also, there may be more than one audience: a general writing a military dispatch, for example, might be thinking both of his superiors at headquarters and the general public.

- What are the main points of the document? This is your summary. What is happening in each section of your document?

Writing a Summary: Typical Process

- Divide the text into sections

- For each section,

- Determine the main point of that section

- Write a one- or two-sentence summary of the section, focusing on that point

- Write a one- or two-sentence summary of the entire piece

- Check your high-level summary against the original text

- Combine your summary of the entire piece with your section summaries into a paragraph

- Check what you have written against the original text

Writing a Summary: Tips

- A summary condenses a text, so it is normally shorter

- Summaries identify the main point of a text and provide information about the supporting points

- Be sure to refer to the author as you write your summary

- In general, don’t quote in summaries

D. Analysis Write-Up

Make an argument about what you think the author wants his or her audience to believe, using three examples from the text.

- Content:

- Start with an introduction paragraph that states what you’re arguing in this essay—that is, what you think the author is really trying to say. What questions does the reading raise about the author’s intent? What clues in the text hint at their motive? What does this author believe in?

- Then, give three examples. For each example, describe what it says in the text, and then talk about what you think the example tells us and how it lines up with what you’re arguing in this essay.

- In your discussion, try to include the answers to the analysis questions below.

- Sources:

- You don’t have to, but you may briefly use information from the books you found for your Annotated Bibliography as support for your analysis. Most of the paper should be what you think—your analysis and interpretation of your document.

- If you do use information from your Annotated Bibliography sources, that information must be cited by adding the author’s name and year from your Annotated Bibliography plus a page number after any information from your sources: e.g., (Smith, 2021, 54). Not providing cites for any information from your sources will result in a grade reduction for the assignment.

- Important warning: You must not use web pages, blogs, Wikipedia, or any other nonscholarly source, credited or uncredited. Use of material from websites or sources other than your document and the scholarly sources in your annotated bibliography will result in a zero for the assignment.

- Formatting: Same as for the Summary Write-Up (see above).

- Length: Your Analysis Write-Up should be at least 1½ to 2 full pages of writing, double-spaced. This is about 500-750 words.

Due date: Monday, December 11

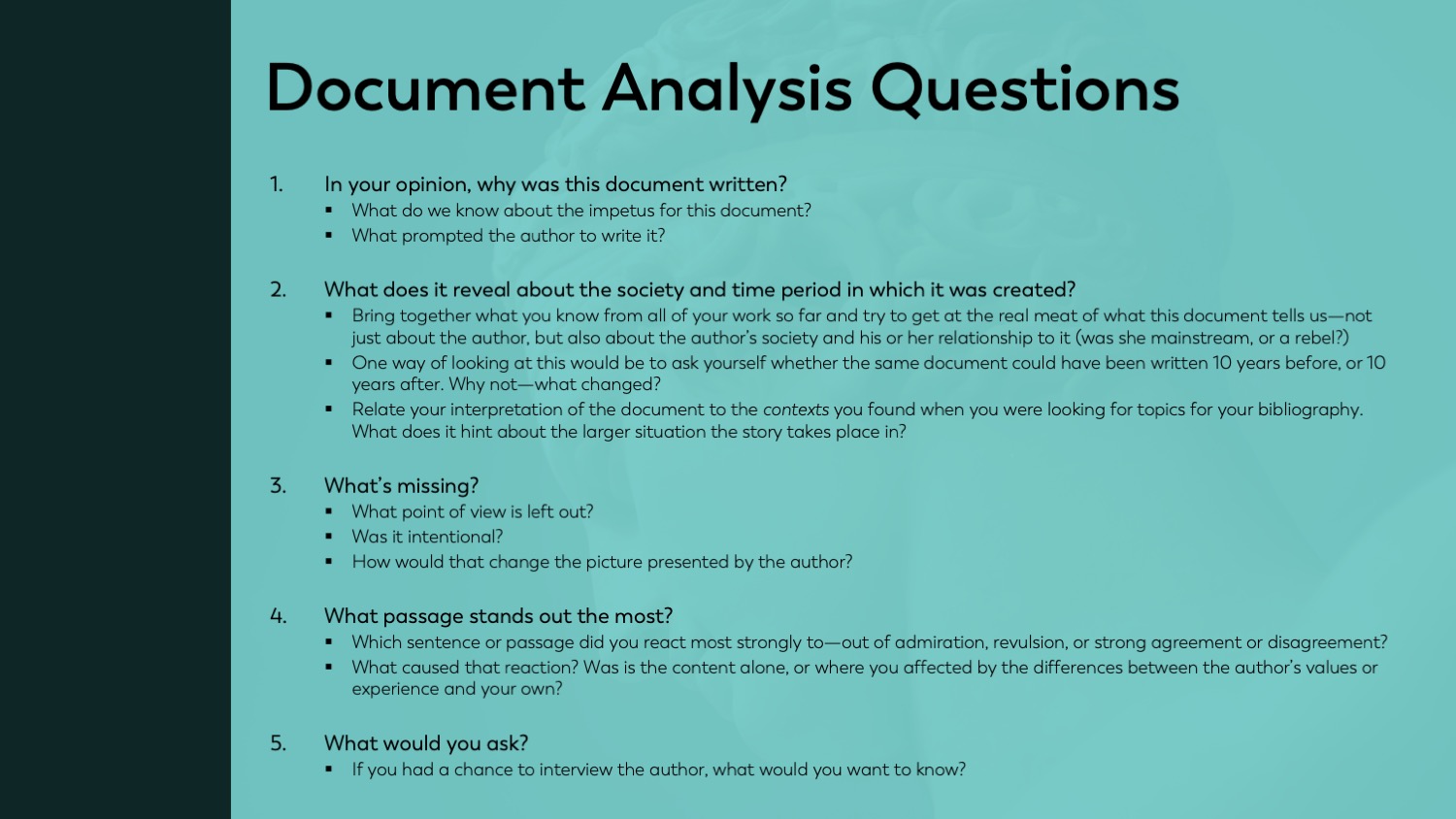

Document Analysis Questions

Once you have a sense of what the document says, you can try to explore what you think it means, based on your reasoning, experience, and the information you have available.

- In your opinion, why was this document written?

- What do we know about the impetus for this document?

- What prompted the author to write it? What can we infer about the author’s intent?

- Often there is a mundane reason and an intent. A speech might be composed because there was an event that required one; a story might be written because there was rent to pay. But these particular words were written because the author had something to say. What was it?

- What does it reveal about the society and time period in which it was created?

- Bring together what you know from your work so far in this document and try to get at the real meat of what this document tells us—not just about the author, but also about the author’s society and his or her relationship to it (was she a part of the mainstream, or a rebel?).

- One way of looking at this would be to ask yourself whether the same document could have been written 10 years before, or 10 years after. Why not—what changed?

- Relate your interpretation of the document to the contexts you found when you were looking for topics for your bibliography. What does it hint about the larger situation the story takes place in?

- What’s missing?

- What point of view is left out? Was it intentional? How would that change the picture presented by the author?

- One way of looking at this would be: How would this storu be different if it were told by someone else?

- What passage stands out the most?

- Which sentence or passage did you react most strongly to—out of admiration, revulsion, or strong agreement or disagreement?

- Think about what caused that reaction: Was is the content alone, or where you affected by the differences between the author’s cultural values or experiences and your own?

- What would you ask?

- If you had a chance to interview the author or the key individuals in the story, what would you want to know?

Slides Relating to the Analysis Write-Up

Click to enlarge images.

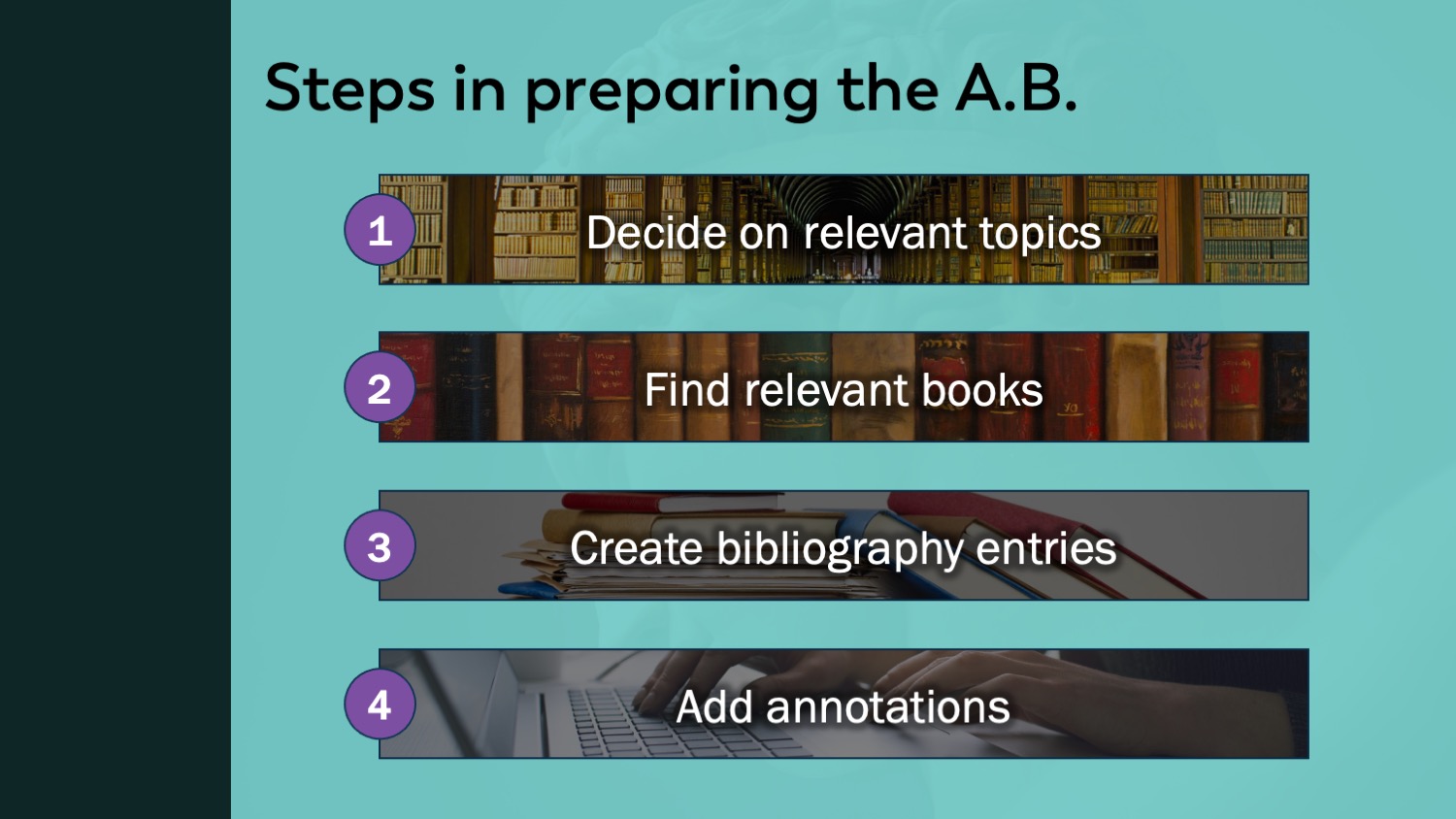

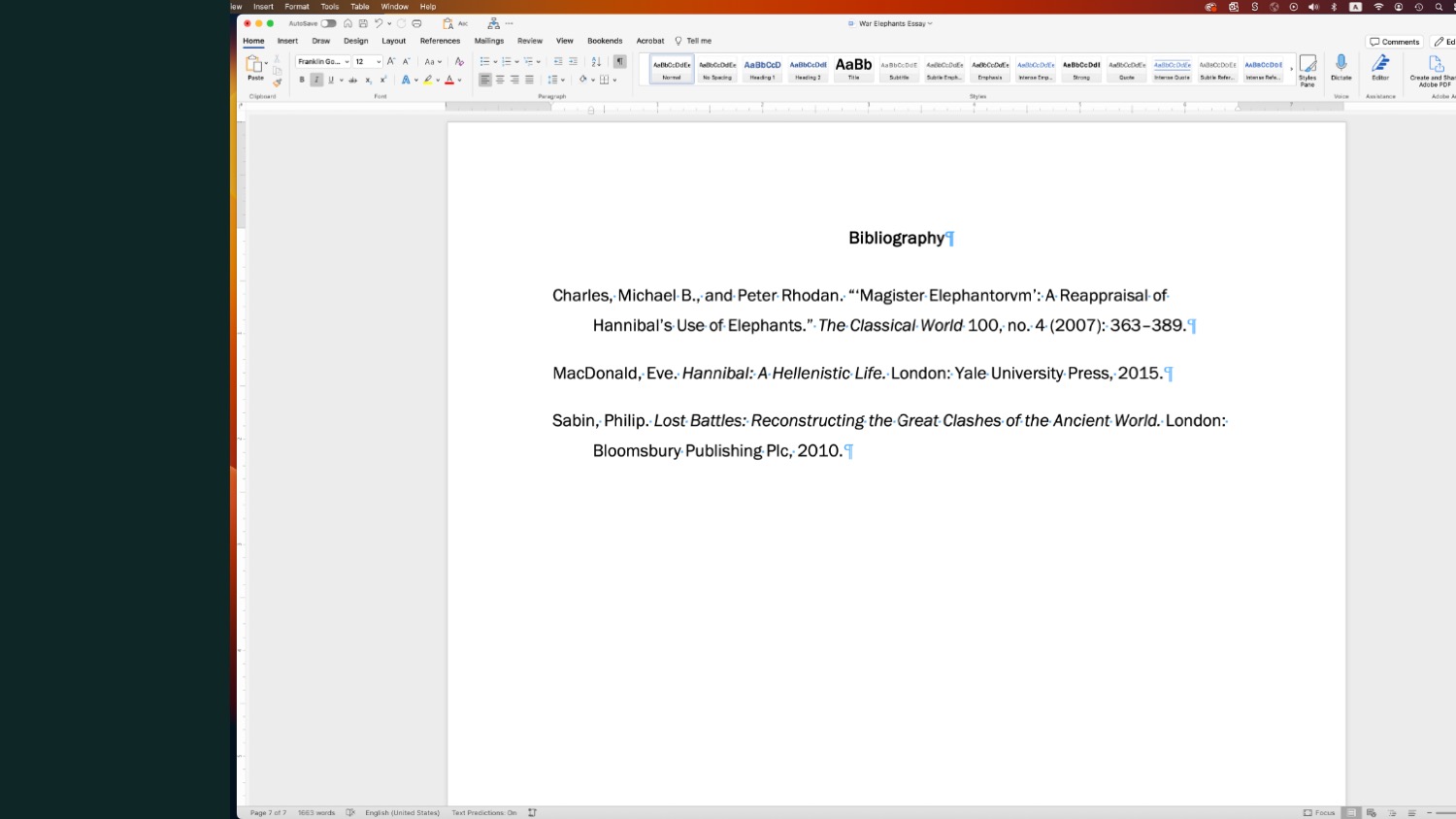

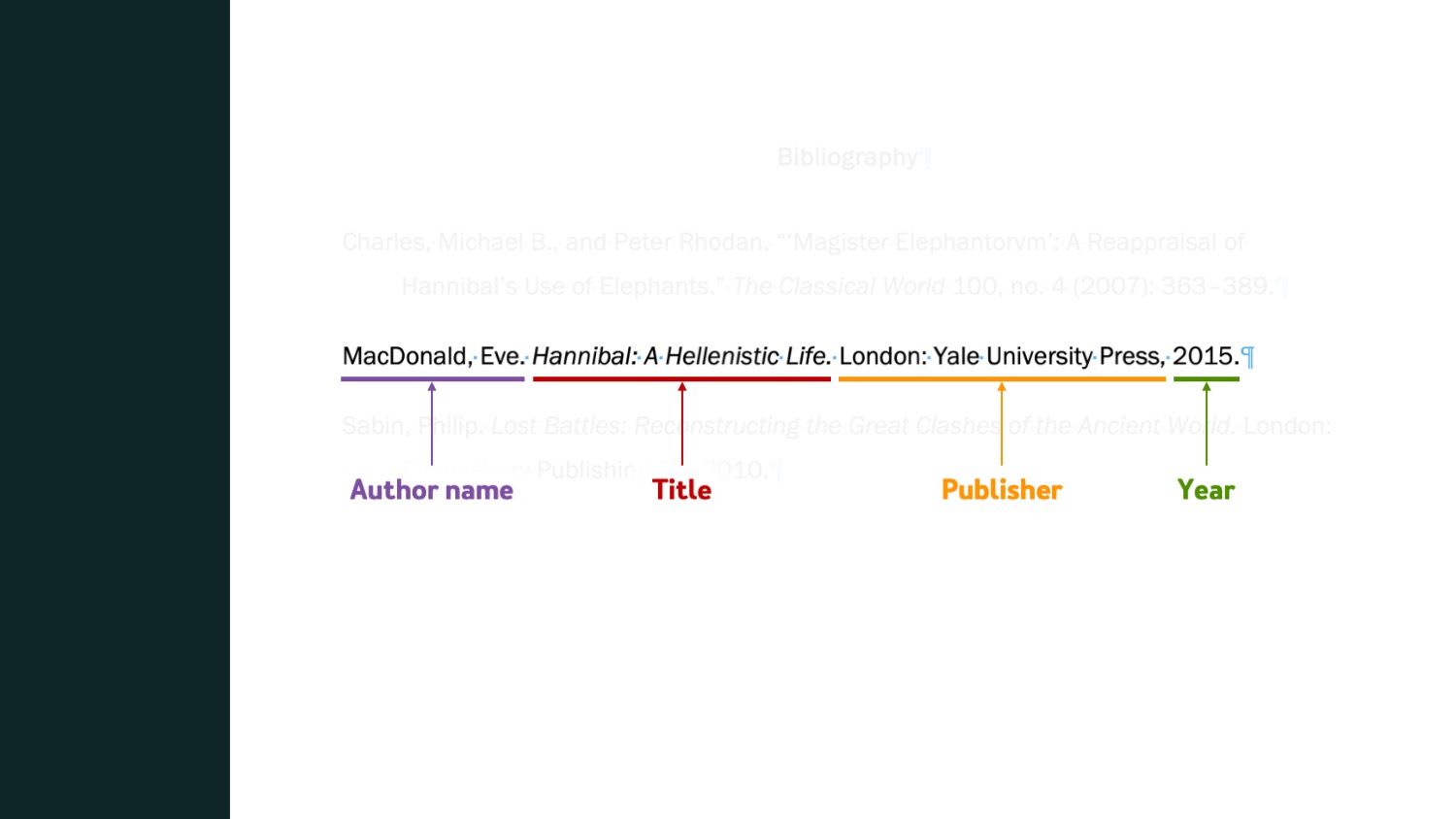

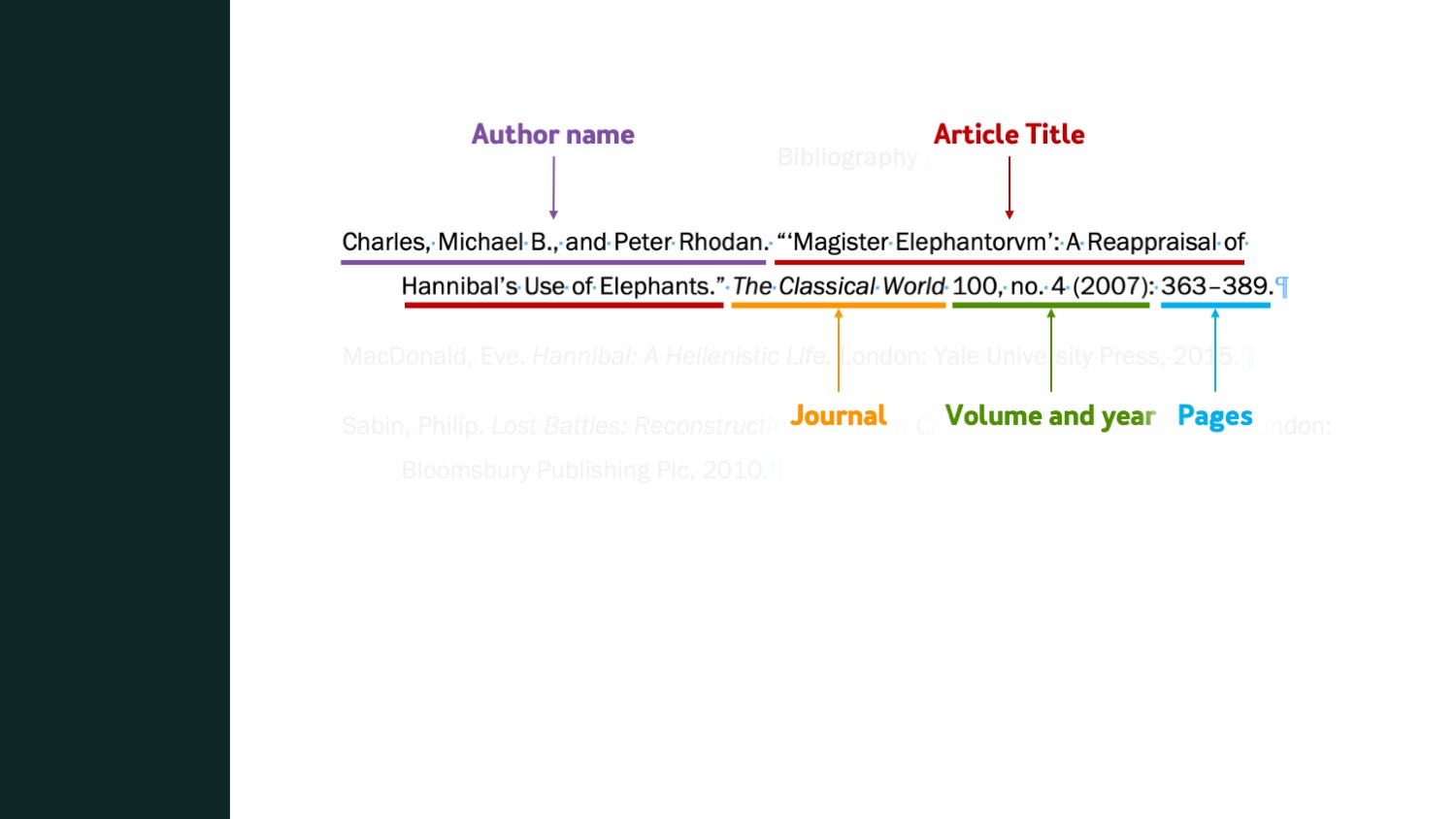

C. Annotated Bibliography

Use the Lehman library website to find three books or journal articles about your document or its context, and write a paragraph for each about why they would be useful.

- Go to the Lehman library website and find three books or journal articles that would be relevant and potentially useful if you were writing a research essay on your document or the time, place, and culture it comes from.

- For each book or article,

- Look through the table of contents, the index, and the publisher’s summary to get a sense of what this work talks about that’s relevant to your document.

- For journal articles and book chapters, skim through the text and look for subject headings and key topics to get a sense of what is covered.

- Use the citation feature on the library web page for that work to copy and paste a bibliography entry into your document.

- Under the bibliography entry, write a paragraph about what this book talks about and why it might be helpful for someone researching your document or the time, place, and culture it comes from.

- Formatting: Same as for the Summary Write-Up (see above).

Due date: Monday, December 4

Process for doing the Annotated Bibliography:

- Choose topics that relate to your document that relate to your document. As discussed in class, these tend to involve:

- The individuals

- The context(s)

- The event

- The text

- Search on these topics on the Lehman Library website using OneSearch and find three digital resources that would help you research your document.

- These can be books, book chapters, and peer-reviewed journal articles. You can filter for these in OneSearch.

- Include only secondary sources (scholars writing about primary sources). No tertiary sources are allowed (textbooks, encyclopedia entries, etc.)

- To check for the relevance of a resource to your document, look through the summary, table of context, chapter titles, and subject heads. You can also check the index to see if your topics are covered.

- Copy the citation for this book, book chapter, or article from OneSearch to your document.

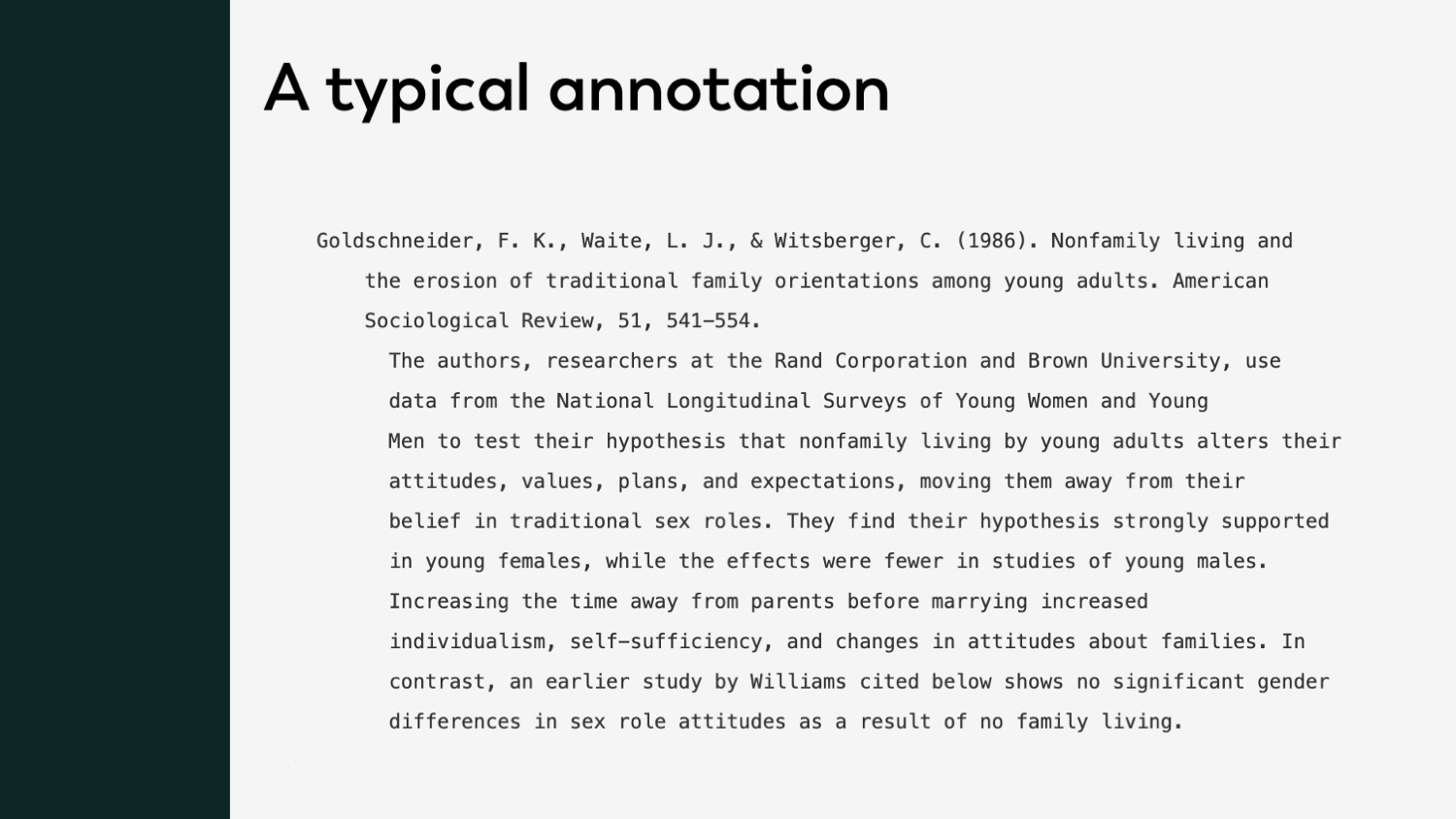

- Write an annotation paragraph under your citation. Your annotations should:

- Start with which of the topics you chose for your document this work relates to

- Include specific subjects in the book/article covered that bear on the research subject

- A brief statement of your opinion of the work’s potential value

- What part of the research subject this book/article helps explain or shed light on

- Potential limitations or problems

- Email your Word, PDF, or shared Docs file to me at mark.wilson@lehman.cuny.edu.

Slides Relating to the Annotated Bibliography

Click to enlarge images.

Reminders

Plagiarism reminder: For your written assignments, you must use your own words and your own thinking. Do not copy or retype anything from web pages about your document, or from anywhere else. Using the words of others without citations as your own is plagiarism, and it’s not tolerated at Lehman College.

For these assignments, quoting from your document is fine—as long as it’s in quotation marks and it’s clear it’s coming from your document. Otherwise, the content of your write-ups must be your words and your thinking.

As stated in this course’s syllabus, any write-ups containing plagiarism—pasting in or rearranging the words of others without citations indicating its source—will result in an automatic zero for the assignment. Multiple instances of plagiarism will result in failing the course.

Late assignments: As stated in the syllabus, late assignments will be accepted, but will be marked down for being late.

A. Choosing your document

This is your Week 11 response and will be posted online. For this, you’ll need to do two things.

- Choose one of the list of short documents from history that interests you. (See list below.)

- Skim through the reading at a glance and see what jumps out at you as you look through it.

- This will be your document for the rest of this project, so pick one that you want to explore or find out more about.

- For your Week 11 online response, write a post that includes all of the following:

- Which reading did you pick?

- Why did it interest you?

- What passage or detail jumped out at you as you glanced through it?

- What, specifically, would you like to find out more about?

Due date: Monday, November 13

Available documents

To start this project, pick one of the short documents listed below and get to know it over the next few weeks, so that you can write about it with confidence.

- The First Civilized Man

- Nausicaa and the Stranger

- The Artifice of Penelope

- The Epic of Gilgamesh: Tablet 1

- The Eumenides: Excerpts

- Abraham and Isaac

- The Book of Ruth

- The Rape of Lucretia

- The Mythology of the Farmer General

- The Samnites’ Linen Legion Remains Undaunted

- On Alexander

- Panegyric Addressed to the Emperor Trajan

- How Didius Julianus Bought the Empire at Auction

- On Charlemagne

- A Romance of Lancelot

- The Rule of Law

- On the Athenian Constitution

- The Allegory of the Cave

- The Ideal State

- On the Subject of Roman History

- Acts of the Divine Augustus

- The Luxury of the Rich in Rome

- The Ancients and Liberty

- The Prince: Excerpts

- Cato’s Speech on the Oppian Law

- Speech of Marius Against the Nobility

- The Virtue of Paganism

- The Speech that Launched the First Crusade

- The Gettysburg Address

- I Have a Dream

- Sayings of Spartan Women

- On Labor

- Advice to Bride and Groom

- Gratian: On Marriage

Stories about People

The story tells of how the Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda asks Yima to convey his law to mortals, but Yima refuses; so Yima instead expands the wealth and prosperity of the world.

During his travels, Odysseus comes ashore alone and bedraggled, only to encounter a beautiful noblewoman named Nausicaa.

While Odysseus is away, his wife Penelope executes a cunning plan to hold Ithaca together until his return.

When Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, abuses his power, the gods respond by sending a wild man, Enkidu, to be tamed by a harlot and befriended by the king.

Orestes is tortured by the Furies for killing his mother—even though he was ordered to do so by Apollo.

The Jewish god, Yahweh, demands that Abraham demonstrate his loyalty by sacrificing his son, Isaac.

After the death of her husband, Ruth moves to Judah with her mother-in-law, Naomi, instead of remaining with her own people.

In the early days of the Rome, an arrogant prince, Sextus, deliberately chooses the most virtuous woman in Rome force himself upon.

Cincannatus, a Roman farmer and senator, is called from his plow to lead Rome’s armies in a time of fear and crisis.

To fight off Roman dominion, the warriors of Samnium warriors make a terrible vow: victory or death.

Plutarch tells a story about Alexander the Great in his youth taming an untamable horse, foreshadowing future greatness.

Trajan, emperor of Rome at the height of the city’s greatness, is praised by one of his governors, Pliny the Younger.

In the later days of Rome’s empire, the question of who might rule was sometimes decided in crass ways.

Einhard describes his friend, the medieval emperor Charlemagne.

Commissioned by his aristocratic female patron to write a romance about Lancelot, a medieval writer tells of the knight’s journey to rescue the kidnapped Queen Guinevere.

Words about Society

Solon, a poet and statesmen who reformed the laws of ancient Athens and made possible its democracy, writes about why the laws are important.

An Athenian sympathetic to the nobles writes about the problems with the democracy of Athens.

In this famous passage, the philosopher Plato suggests that humanity is deluded by shadows of the truth.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle describes what the best possible government might look like.

A Greek historian defends his study of the history of the Romans and why they stand above other peoples.

The emperor Augustus reflects on his accomplishments after a long reign.

A Roman historian details the decadence of the city of Rome a century before it fell.

A thousand years after the fall of Rome, Niccolo Machiavelli discusses how stubbornly the Romans defended their liberty.

After being exiled from Florence, Niccolo Machiavelli explores what is required for a prince to be truly effective as a ruler.

Calls to Action

Cato the Elder, a Roman senator, speaks passionately against the repeal of a law forbidding women from wearing jewelry and rich clothing.

The populist Roman general Marius denounces the Roman nobility for endangering Rome by keeping themselves in power regardless of ability.

A generation after the Roman Empire and its rulers turn to Christianity, the emperor Julian argues for a return to pagan ways.

When the Byzantine Empire is threatened by Turks, a medieval pope calls for a war of Christians against heathens, promising rewards in heaven for those who fight on Christ’s behalf.

While dedicating a cemetary to the war dead of the Battle of Gettysburg, President Abraham Lincoln concisely describes what the Union troops are fighting for in the American Civil War.

Martin Luther King Jr. speaks eloquently on what America could be if people of good will fight for it.

Perspectives on Domestic Life

An ancient author collects the sayings of the wives and mothers of Sparta.

The ancient Greek writer Hesiod discusses what makes a farmer successful.

Ancient Greek writer Plutarch discusses what’s truly important in making a marriage happy and long-lasting.

A medieval theologian defines marriage in Christian terms.

Alternative documents: If you are strongly interested in using another primary source document from history, it is possible to do, but you need to send me a link to the text of the primary source and ask my permission first. If it turns out that the document you’re interested in isn’t suitable for this project, you’ll need to go ahead and pick one of the texts above as your document for this project.